We Need Your Help Building the First Universal Tool to Measure Human Connection

A Universal Tool to Measure Human Connection

Right now, researchers and health organisations worldwide are trying to solve a global loneliness crisis using measurement tools that work for maybe 12% of humanity. These tools were built primarily for white, educated people in the West, then applied everywhere else as if all cultures experience connection the same way.

They don’t.

We’re building something different: a measurement tool for social connection that works across cultures. But we can’t do it alone. We need people from around the world to help us write questions, test our ideas, and make sure this tool captures how connection really works in different communities.

The Problem: Measuring Connection with the Wrong Tools

Current measurement tools create a distorted map of human connection. They spotlight certain types of connection while rendering others completely invisible. For billions of people, connection is inseparable from duty, spirituality, place, and tradition. It flows through relationships that current measurement tools can’t even detect – such as prayer with deceased ancestors, the emotional weight of caring for extended family networks, cyclical community gatherings that create belonging.

The World Health Organisation has declared social isolation and loneliness global health threats, and governments worldwide are spending billions on interventions. But the measurements driving these decisions miss how most of the world actually experiences connection.

What We Found: Stories That Challenge Everything We Thought We Knew

Measuring the inner lives of human beings is one of science’s most profound challenges, a task we have often approached with more hope than rigor. While our field has built an incredible body of knowledge, our tools for measuring something as abstract as human connection does not seem to be up to the task of capturing its vast, global complexity.

This is a critical gap. Many of the tools we rely on were shaped by a narrow worldview, leaving them blind to how most of the world actually experiences connection. That limitation is not accidental, it stems from the way scales are often built: by brainstorming items that “seem relevant” rather than grounding them in a deeper understanding of the construct. This ad-hoc process can lead to scales that work for the population they were developed on, but fail when applied to different cultural groups, because the underlying construct was never deeply investigated across diverse contexts.

To build truly universal tools, we need to start with a deep investigation into the fundamental nature of what we’re trying to measure, in the way that all great science does.

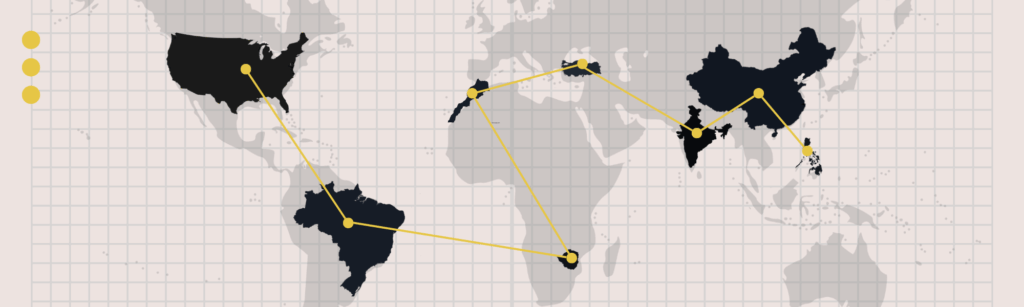

Over the past year, our research teams therefore conducted 350+ in-depth interviews across eight countries: Brazil, Zimbabwe, India, Philippines, Morocco, Turkey, China, and the United States. Each interview lasted 2-3 hours, with structured questions that were designed from the ground up by interviewers from each of the countries. We asked people to describe their connection in their own words.

Here are some of the stories that emerged – preliminary insights that will be fully analysed in our forthcoming academic publications:

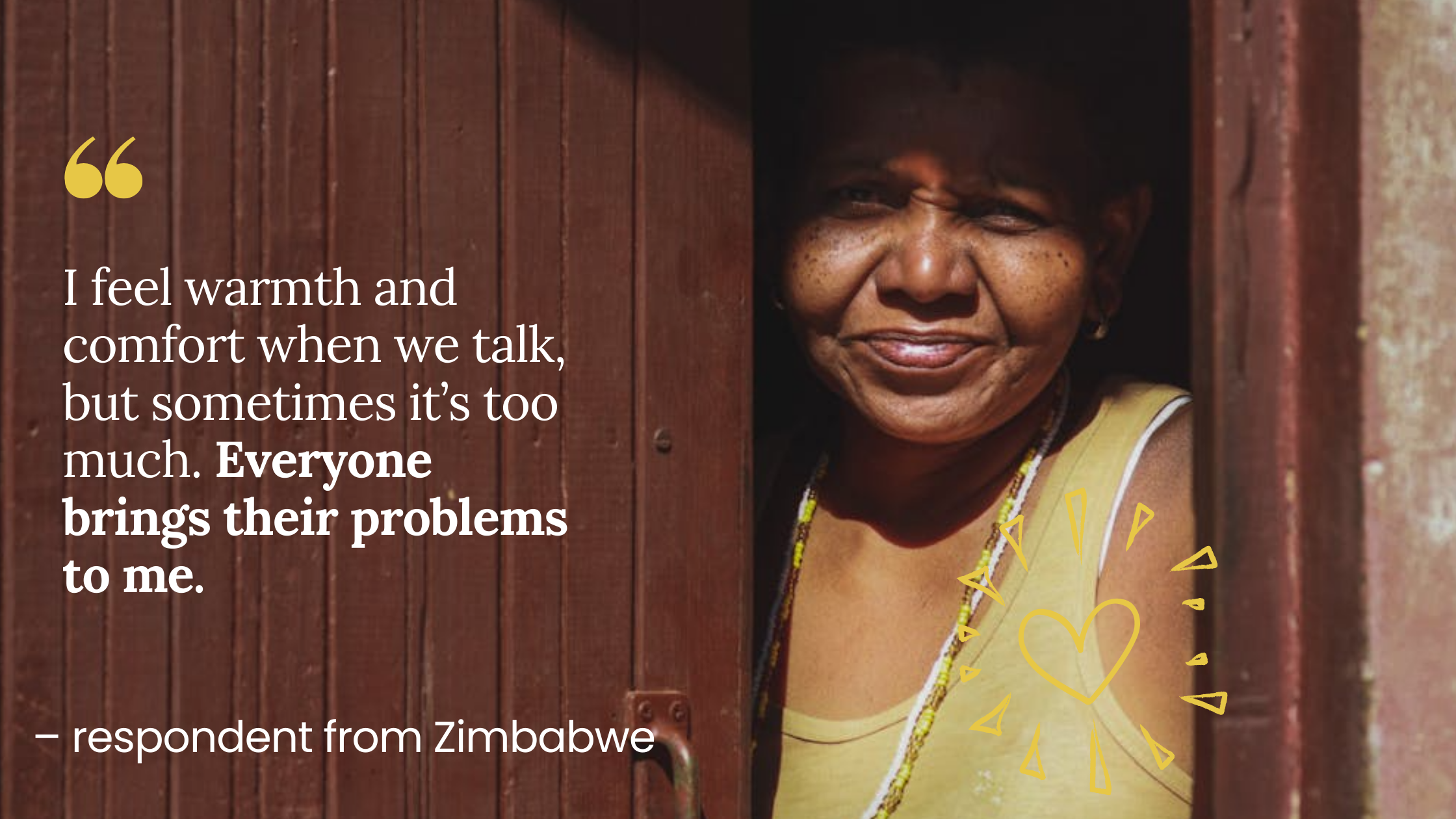

- In Zimbabwe, we discovered a profound pattern of gendered emotional labour. Older women consistently described carrying the emotional weight of entire extended families. One participant said: “I feel warmth and comfort when we talk, but sometimes it’s too much. Everyone brings their problems to me.” This wasn’t isolated to one person. Across interviews, we heard about grandmothers who serve as community emotional centres, absorbing neighbours’ pain about troubled marriages, and family conflicts. Yet this same pattern manifested completely differently elsewhere. Brazilian mothers described managing complex diaspora family networks across continents, while Turkish women spoke about balancing family duty with personal autonomy.

- The Philippines revealed profound contradictions between cultural expectations and inner emotional reality. Despite the country’s reputation for strong community bonds and family orientation, participants described feeling emotionally disconnected even while maintaining active social lives. One person shared: “I choose not to speak, because they won’t understand.” Another explained how cultural expectations create an additional burden: “Filipinos often appear cheerful even when sad – a coping mechanism.” The pressure to maintain a “happy-go-lucky” demeanour means that loneliness often gets “hidden behind appearances” or “masked by cheerfulness,” creating what we termed “invisible isolation” within seemingly connected communities.

- In Morocco, Turkey, and India, participants repeatedly described forms of connection that our Western measurement tools don’t even recognise. Prayer emerged as a powerful connector not just to the divine, but to deceased family members and communities across distance. One Moroccan participant explained how this spiritual connection feels more real than many living relationships. In India, religious practices served as crucial coping mechanisms when participants felt lonely: “When I feel lonely, I read the Quran, I pray, and I ask Allah for help.” These spiritual dimensions of belonging – central to how many cultures understand connection – are entirely absent from tools developed in the Global North.

- Chinese participants opened our eyes to the profound importance of place-based connection that research in the United States and Europe rarely considers. “I have been in my hometown for 19 years, so I have a very deep sense of connection” one person shared. Others described feeling fundamentally displaced when away from their ancestral communities, regardless of social relationships in their new locations. This geographic anchoring of belonging emerged as crucial yet is rarely measured in existing connection research.

- In India, we found that family dominated every single participant’s account of social relationships (100% mentioned family as central), yet this came with complex gender expectations. Women participants described unique burdens: “There are so many women in our country. They will feel lonely. They will suffer. Only women can bear the suffering.” Meanwhile, cultural expectations discourage men’s emotional expression with messages like “don’t be too emotional, don’t share too much.”

- Turkey revealed how connection extends far beyond human relationships to include places, nature, and even aesthetic elements. Participants described emotional bonds with specific locations, natural settings, and sensory experiences: “It could be anything – flowers, the weather, sounds, lights, everything.” This broader conception of connection rarely appears in psychological research in the United States or Europe.

What We’re Building: A Modular System for Different Needs

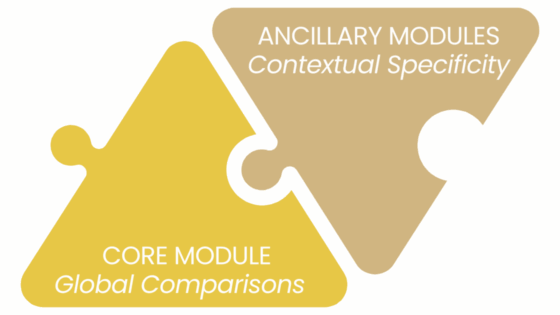

Based on these findings, we are creating a culturally-responsive measurement system for social connection with three components:

- A single-item assessment for quick screening.

- A 10-item core module for global comparisons across all cultures.

- A 10-item ancillary module tailored to specific cultural contexts.

This allows organizations like WHO and OECD to make meaningful global comparisons using core items, while enabling local researchers to capture cultural specificities through ancillary modules.

The core module will focus on universal dimensions that emerged across our interviews while being expressed differently in each culture – like emotional support, trust, belonging, and reciprocity. The ancillary modules capture culturally specific elements like spiritual connection, place-based belonging, and traditional practices that matter deeply in specific communities but don’t translate universally.

Both approaches reflect how people actually experience connection, grounding the measures in dimensions our global research revealed that current scales consistently miss.

What We Need From You

We’re looking for people worldwide to help us with two essential tasks that will determine whether these tools actually work for diverse communities.

- Item generation – How do we create questions that better capture people’s experiences? Current loneliness scales ask things like “How often do you feel left out?” But what if “left out” doesn’t translate meaningfully in your culture? What if the real question should be about spiritual disconnection, family burden, or community obligation?

When a participant describes their experience as “I feel warmth and comfort when we talk, but sometimes it’s too much. Everyone brings their problems to me,” this insight could become an item like: “Sometimes caring for others’ emotional needs becomes too much for me to handle.” That’s the kind of culturally grounded insight that can transform how we measure human experience.

- Cultural review of our developing questions – As we create draft items, we need people to tell us when we’re getting it wrong. Do our questions make sense in your cultural context? What assumptions are we making that don’t fit your community’s reality? We need people willing to look at our work and say: “This makes no sense in my culture” or “You’re missing the most important part.”

Why Your Cultural Knowledge Matters

Most psychological research is based on samples from the United States or Europe (often referred to as “the Global North”). That represents about 12% of the world’s population, but it shapes 96% of psychological research. This means that the vast majority of what we “know” about human connection comes from studying a tiny, unrepresentative slice of humanity.

But even for people in the Global North, not everyone has been represented. Your understanding of how connection works in your community is therefore essential. Whether you’re a grandmother in rural Scotland who understands how caregiving shapes relationships, a techie in London navigating digital connection challenges, a student in Birmingham balancing multiple cultural identities, or a retiree in Manchester discovering new forms of community after decades of change, your experience matters for building tools that work for everyone.

Current tools miss so much of the human experience – spiritual connection, extended family complexities, bonds to places, cultural rituals, and gendered emotional labor – making much of today’s research irrelevant to most of the world.

How to Get Involved

There are several immediate ways you can contribute to this work, depending on your background and interests.

- If you’re interested in item generation, you can help us write questions that capture authentic connection experiences in your cultural context through our survey.

- For cultural review, we need people willing to review, again through a survey, our draft questions. This is particularly valuable if you have experience living between cultures or working with diverse communities, as you can spot assumptions that might not be obvious to researchers.

Ideally you can do both.

For researchers reading this, we need help collecting samples in all kinds of populations.

Ready to help?

Contact us to learn about specific ways you can contribute.

Want updates?

Join our ABSL mailing list to hear about opportunities to participate or just to learn more about our work as we develop these tools.

Beyond direct participation, you can help us reach diverse voices within your cultural or geographic community – parents, teachers, community leaders, religious figures, social workers, anyone who understands how relationships function in your community. Just share this post with them. The more diverse voices we include, the better these tools will be, and the more lives they’ll ultimately serve.

This is our chance to build measurement tools that finally capture the full human experience of connection, and we can’t do that without you.

Biographies

Dr. Hans Rocha IJzerman

Dr. Hans Rocha IJzerman is a behavioral scientist specializing in social connection, social isolation, and loneliness. He co-leads the development of a monitoring framework to assess loneliness across the European Union and supports global initiatives in psychometric reform, including large-scale, multi-country studies on social health. A pioneer in AI-powered, personalized assessment tools, Dr. IJzerman works closely with policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to translate scientific insights into practical solutions. He is also a leader in the scientific reform movement and an advocate for open, evidence-based approaches to improving social well-being.

Sharanya Mosalakanti

Sharanya Mosalakanti is a Junior Researcher at Annecy Behavioral Science Lab, where her work focuses on psychometrics, social connection, and the development of innovative approaches to psychological assessment. She holds a Master’s degree in Industrial-Organizational Psychology and has experience in assessment design and adaptive testing methods. Her current research explores how loneliness and social connection can be understood and measured across diverse populations.

Responses