Speaking with Severely Lonely Residents in Tower Hamlets

Since 2017, Tower Hamlets Council has been working with local organisations, NHS partners and voluntary groups to tackle loneliness. This project was commissioned by the Public Health team to help strengthen that work, especially in relation to residents facing the most severe and long-lasting forms of loneliness. It feeds into the Tower Hamlets Connection Coalition and supports the Council’s wider Tackling Loneliness Strategy.

Neighbourly Lab led the research, aiming to understand how well current services are working, identify gaps, and co-develop ideas for how support can improve.

“You’ll always feel lonely when the person you need to be with isn’t here.”

Tower Hamlets resident”

How we did the research

We spoke to 12 residents with lived experience of severe loneliness from different parts of the borough. Some were referred to us by frontline workers who had identified them as particularly isolated. We also interviewed 17 local stakeholders involved in delivering support, from social prescribers and care navigators to voluntary sector groups and housing staff.

Alongside this, we reviewed existing research and data, and ran a workshop with stakeholders to test and refine our findings. This work doesn’t claim to be comprehensive, but it does give a meaningful snapshot of what severe loneliness looks like in Tower Hamlets today and what might help. Severe loneliness showed up in different ways. It wasn’t always visible, and it didn’t always mean being physically alone. But across the conversations we had, three patterns came through clearly.

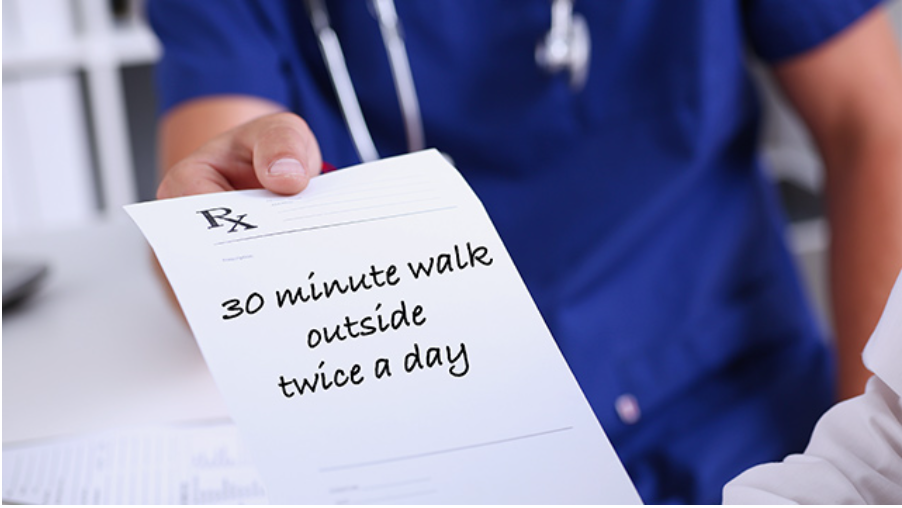

The first group were housebound. These residents rarely left their homes due to poor mental or physical health. Some were recovering from strokes or dealing with chronic pain. Many were living with depression or anxiety that made it difficult to go outside. Their days were quiet and repetitive, with little contact beyond care workers or the occasional phone call. Several said they hadn’t been in a social setting in years and felt like the world had forgotten them.

The second group were more active. They went to shops, joined community classes or exercise sessions, or attended lunch clubs. But even when they were around other people, they still felt alone. They spoke about polite conversations or routine interactions that didn’t go any deeper. Some said they went out just to avoid sitting in silence at home:

“I go to lots of places and activities, but I’m still very lonely. Sometimes I just go to be around people, even if we don’t talk.” Tower Hamlets resident.”

The third group felt overwhelmed. These were often unpaid carers, looking after elderly relatives, disabled children or partners with health issues. They had very little time to themselves and were carrying a heavy burden of responsibility.

Even if they had people around them, they didn’t feel supported. Many said they hadn’t had a proper break in years and had no one checking in on them:

“I have no memory of a happy time since I came to the UK. It’s been a struggle throughout.” Female carer, Tower Hamlets”

We also heard about other situations that made people feel isolated. Some had lost contact with family or had loved ones living abroad. Others felt surrounded by people but had no one they could really talk to or rely on:

“My friends in London now all have families and children.

They don’t really have time for me anymore.” Tower Hamlets resident”

Housing, language and confidence also came up again and again as issues which compounded loneliness. A few people said they didn’t feel part of their neighbourhood anymore. They talked about gentrification and rising costs, and how things had changed around them. Some felt left out of groups because of cultural differences or not speaking English confidently. Others mentioned struggling with forms, booking appointments or going online:

“Half the houses on my road have gone private now. There’s not much community spirit left.” Lifelong Tower Hamlets resident”

Some of the residents we spoke to had once been very active. They had jobs, raised families or ran local groups. But over time, things had shifted. Illness, bereavement or other changes had left them feeling cut off. They weren’t sure how to re-join things or where to start:

“I used to fix things. Last thing was a brooch for my wife, but she passed away before I could give it to her. Haven’t fixed anything since.”

These stories showed us that severe loneliness isn’t just about being alone. It’s about losing confidence, losing purpose and feeling like you’re no longer part of things. For many, that feeling had built up over years.

Where more support could be on offer

There are already a lot of amazing, life-changing projects happening in Tower Hamlets, coming from the voluntary sector, the NHS, council services and residents volunteering themselves, but the system as a whole doesn’t always reach people facing this depth of isolation.

Some residents are not being found. They may not identify as lonely or feel comfortable asking for help. Others are visible to services but still falling through the cracks. The support that is available isn’t always the right kind. Residents often need more than just an activity. They need consistent, tailored support that helps build confidence and social connection over time. Many organisations doing this work are overstretched.

Services aimed at specific groups, like older Bangladeshi women or LGBTQ+ residents, often lack capacity. Practical issues like inaccessible housing, unreliable transport and underfunded social care services make it harder for people to stay connected, particularly those who are housebound.

“Having a hot meal is like Christmas for these residents.” Stakeholder working with housebound clients”

Some people do access support but feel it doesn’t reflect who they are or what they need.

“I’ve tried groups before, but they’re not for me.

I don’t want to sit around talking about children or cooking.

I want to be around people like me.

What needs to happen next

Better identification and first contact

Professionals across housing, health and social care need time and training to spot loneliness and respond early. Community-led approaches, including neighbours, local businesses and grassroots groups, also play an important role. Reaching people should not rely on them asking for help first.

Co-creating services with residents

Support works best when it is shaped by the people who use it. That means involving residents in designing and running activities and making sure they reflect different cultural needs, languages and life experiences.

Tailored, practical support

Some residents need hands-on support to navigate services, build confidence or even just leave the house. A skilled, consistent befriender-plus model offering emotional support alongside practical help could make a big difference.

A more joined-up system

Services need to be better connected so people do not get stuck at one stage or fall out of the system altogether. Long-term funding is essential so organisations can build trust and respond flexibly, not just deliver short-term projects.

“Fifteen years lost. Now I’m catching up on life”.

Conclusion

Severe loneliness doesn’t look the same for everyone, but it always has deep emotional and practical impacts. It can sit quietly behind closed doors, even in busy neighbourhoods. What we heard from residents is that they want to feel seen, listened to and part of something. That requires time, trust and the right kind of support.

With the right focus, funding and coordination, local authorities can lead the way in showing how to respond to loneliness with care, creativity and commitment.

Biography

Jake Preston

Jake is a senior researcher at Neighbourly Lab & Project manager for The Tackling Loneliness Hub.

Working across a variety of projects providing logistical and research support for clients he evaluates community assets from a variety of resident perspectives. Jake works closely with the business development team, supporting with developing project plans and proposal refinement.

Jake also has a keen interest in how the built environment impacts the way communities connect with one another and applies this in helping to develop our social infrastructure focus area. He also supports with the expansion of our social connection evidence base and works closely with their Social Connection Evidence Gathering team conducting desk research and developing reports.

Responses