Loneliness can be useful, but only if we target our response to it properly

Harry Hobson, Founder and Director of the Neighbourly Lab, shares findings from the Reconceptualising Loneliness in London report and how we can effectively target our response to loneliness in London.

Severe loneliness is an alarm call about social disconnection

Whether you are one of the 8% of people who are severely lonely or not, we all know that feeling severely lonely is horrible and painful. And of course as policy-makers and practitioners, we are looking to remove the causes of the pain and to reduce its effect.

But, let’s pause for a moment to acknowledge and hear this pain because of what it signals to us. Let’s let the pain do its job for us. According to evolutionary-biology, we animals feel pain because it helps us adapt our behaviours or modify our environment. Like thirst or hunger, severe loneliness is an aversive pain, alerting us to alter our behaviour or change our environment.

John Cacioppo wrote “Loneliness is not a pathology. It’s just an external signal from our body that something is going wrong with our environment.” But there’s something unique about this particular pain. With most pains, the person who feels it can act to remedy it. If you are thirsty, you have yourself a drink. But what’s unique about the pain of severe loneliness is that whereas the aversive stimulus is felt by the individual, it’s all of us collectively that have to react and respond.

And let’s be clear: something that’s wrong with our environment is that the way Londoners are living together is inadequate and urgently requires repair. The key finding in this report is that severe loneliness is unequally distributed. It falls disproportionately amongst people who already have disadvantages or for whom life is particularly difficult. The way the social fabric of this city is set up works well for most of us most of the time, but terribly for some of us – for some of you right now, or your partners or children or friends.

So at a personal level, feeling severe loneliness is horrible. But at a societal-level it is good and useful if it urgently alerts to a need to act to rebuild London’s connective-tissue and to redress underlying inequalities.

So, as researchers, we are thankful to the Londoners who told the survey that they’re always or often lonely. And as policy-makers, let’s honour them by not ignoring their pain and by collectively responding to it.

How to target our response to loneliness

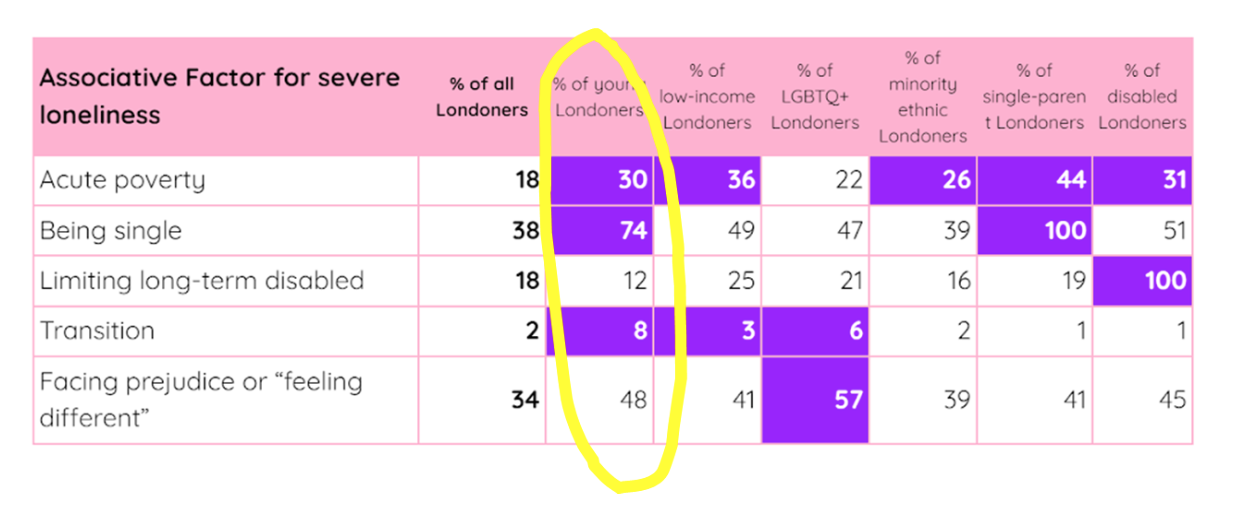

The most useful part of this report is the data-analysis that reveals the “big five” associative factors for severe-loneliness: going through life-changes or being new in London; being acutely poor, being single or living alone; experiencing prejudice; and being disabled or deaf.

In simple terms, our data-scientists asked “what else is going on in the lives of the 700,000 Londoners who are severely-lonely?” This research was obviously in London, but we believe that these Associative Factors apply everywhere.

None of these are surprising. Severe loneliness is the feeling that comes when you face tough times without enough supportive people around you. The more likely you are to face tough times (such as if you are acutely poor or if you are newly-arrived to London) or the more likely you are to not have enough supportive people around you (such as if you are single and live alone; or have a disability that makes socialising hard, or you feel excluded from the community around you), the more likely you will experience severe loneliness.

But what is surprising is that so many interventions to tackle loneliness are not guided by these factors, and therefore miss people they should be reaching, or do not make the most of scarce resources. The main cause of mis-targeting is when organisations look at loneliness through the lens of demographic groups or by protected characteristics. This leads to exaggeration of the problem and generalisation of the treatment.

Let’s take young people for example. According to the survey-data, 12% of young Londoners (16-24 year olds) are severely lonely, much higher than the 8% city-wide. And this is because people in this age-group are more likely to be affected by the “big-five” factors.

As the table above shows, the percentage of 16-24 year olds who are acutely poor is 30% and they are about twice as likely to be single and four times more likely to be in their first year in London. We can therefore start to see why a particular segment of these young people are severely lonely, and best of all, we can see where and where not to target preventative-measures.

So our call to everyone engaged in reducing loneliness is to be more laser focused in your targeting, particularly by:

– Focusing on severe-loneliness, not mild loneliness.

– Targeting according to these “big-five” associative factors, not according to demographic-group.

About Neighbourly Lab

We (Neighbourly Lab) are a research and evidence organisation focused on innovative ways to massively increase social – connectedness.

We are a non-profit organisation and we are based in the Evidence Quarter alongside our neighbours and co-authors on this report, the Campaign to End Loneliness and the What Works Centre for Wellbeing. Thank you to the brilliant team at the GLA Social Integration team for their commissioning and working with us on this report.

Responses