Loneliness in life stories by Chinese older migrants in the UK: A linguistics ethnography

Olivia (Xuechun) Xiang is a sociolinguistic PhD candidate at Queen Mary University of London. In this blog post, she introduces her research on how elderly Chinese migrants narrate their experiences of loneliness in life stories.

A sociolinguistic study

This research examines how Chinese older people living in the UK perceived and experienced the feeling of loneliness in their life trajectories. As a sociolinguistic study, this project will not be developed in a psychological way but will focus on the linguistic devices participants adopt to position themselves when they narrate their stories. In particular, I hope to pay extra attention to the language attitudes and choices of the older people who self-identified as Chinese but do not speak Cantonese as their first language (the reasons for setting this criterion will be introduced in the following part).

Research backgrounds

As for the variations in loneliness across age groups, according to the survey on the prevalence of loneliness, loneliness is seen as an issue that is particularly associated with old age (Victor & Yang, 2012). In older adults examined in past research, twenty to forty per cent of whom have reported feeling lonely (De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg,1999), and five to seven per cent reported feeling persistent or intense loneliness (Victor et al., 2005).

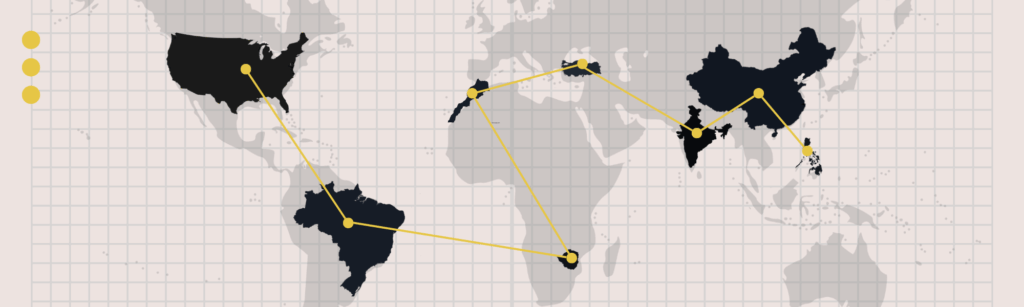

Among the older people, a particular group requires particular attention. In this increasingly globalised world, ageing in a foreign land is part of the late-life experience of many elderly adults (De Jong-Gierveld et al., 2015), who may encounter challenges of active ageing because of the intersectionalities of immigrant status, language/culture differences (Keating & Scharf 2012).

Yet it is regrettable that older migrants are one of the neglected groups in loneliness research as they are a hard-to-reach cohort, especially for ‘outsiders’ (Fokkema & Ciobanu, 2021). The limited studies on older migrants’ loneliness indeed reveal that compared to older adults without a migration background, they are at greater risk of suffering from loneliness (Fokkema & Naderi, 2013; Wu & Penning, 2015).

In terms of the Chinese people in the UK, several key intra-ethnic divisions are worth noticing. The public perceptions have always ignored the heterogeneity of the British Chinese community, in terms of their migration and settlement pattern, language use habits, and social and economic status. In the UK, Chinese communities were traditionally dominated by Cantonese-speaking mid-century arrivals from southern China, who were pre-handover Hong Kong and Sino-Vietnamese refugees.

However, since the 1980s, a number of highly educated professionals from mainland China, Commonwealth Malaysia and Singapore started a wave of migration that shifted the demographic balance of the Chinese diaspora. Later in the 1990s, legal and illegal employment from China’s Fujian Province flowed over into the UK, working as low-skilled and low-wage labour in an established Cantonese-owned economy. While most of the Chinese migrants self-identified as Chinese when they arrived in the UK, their language repertoire and flexibility were distinct.

For example, most migrants from mainland China could only speak Mandarin and basic English; some Chinese migrants from Singapore and Commonwealth Malaysia speak Hokkien, Hakka or Teochew, while some are conversant

in fluent English, Mandarin, and Cantonese. Not having a common-used spoken language among the Chinese people from different origin countries/districts greatly inhibited communication and commonality, further leading to the feeling of loneliness of different Chinese subgroups, especially those non-Cantonese speakers.

At the same time, with the influx of educational migrants from mainland China in the last two decades, the language hierarchy between Mandarin and Cantonese in British Chinese society is changing. How do the participants construct their identities in the context of migration and language hierarchy change? Will their identity construction and the feeling of loneliness interplay and in what way? This project will explore these questions by examining the loneliness embedded in the participants’ language practices.

Future research

Currently, I am visiting a Mauritius Chinese older people’s club regularly to conduct observations. This group of older people were born in Mauritius, with parents or grandparents from Meixian (in Guangdong, China), and migrated to the UK when they were in their 20s. As Mauritius is a pre-France and British colony, Mauritius Chinese speak Creole French, standard French and English as their common languages. Additionally, being born into Hakka-speaking families, most of them inherited Hakka from their parents. With such a unique language repertoire and migration backgrounds, how will this group of people be unified, and find their places in British Chinese society? I look forward to hearing their experiences and will keep the readers posted on the research progress.

Follow on Twitter @XiangXuechun if you are interested in her project.

This is a really fascinating read bringing out the richness and variety of the British Chinese community. I hadn’t appreciated quite how many languages would be spoken.